My first Mac, an original G4 mini, hasn’t seen much use since my new iMac arrived last summer. Hoping to start “spare-time” developing again, and now addicted to version control through work, I made it my goal one afternoon to get Subversion running between the old and the new. Eventually I’d like to expand this beyond source code to a home directory or even a .Mac backend, depending on what Leopard ends up offering.

Apple has an article on compiling a full SVN stack on OS X for use with Xcode. This looked a little bit more painful than I was aiming for, for some reason involving hand-patching Apache 2.0 and plenty of configuration. That route is spelled out nicely (), but I wanted something even simpler.

Enter Martin Ott and his ready-made Subversion installer packages. Here’s how you can set up your own low-carb Subversion system, hopefully in less than 30 minutes.

Install SVN

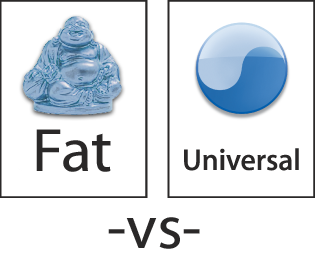

Download the SVN package and install it on both your server and your client machines. It will ask you for your password, and then install several binary utilities in /usr/local/bin. This does not include any Apache modules but it does include a standalone daemon named ’svnserve’. This means no WebDAV access, but you can easily use svnserve with ssh to access your data securely across a network.

Configure paths

Unfortunately, programs in /usr/local/bin aren’t easily used by default. The next step is to get the utilities into your Terminal path. On your client machine, just add export PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/bin to your ~/.bash_profile file. For access via SSH to work, the server needs that same line but added the machine-wide /etc/bashrc configuration instead of your user’s profile. For this, you will need administrator privileges, something like sudo pico /etc/bashrc should do the trick. (Alternatively, you could cd /usr/bin/; sudo ln -s /usr/local/bin/svnserve to avoid editing bash’s global configuration. In this case, also configure your user account on the server just as you did the client, because in the next step we use another utility via that path.)

Make a repository

The repository is where all your past and present data will be stored on the server, accessed via the SVN tools. Pick a spot where you don’t mind an extra folder sitting around, and execute on the server machine: svnadmin create ~/repository. Feel free to change the path, as given it will make a new “repository” directory in your home folder and fill it with files. These internal files should generally not be used directly, we’ll test the SVN commands in the next step.

Accessing the repository

Make sure you have “Remote Login” enabled in System Preferences > Sharing on the server machine. If not, enable it, and you should be ready to go back to the client machine. “Check out” your new (empty) repository with this command: svn checkout svn+ssh://your-machine-name.local/Users/yourname/repository new_local_folder. After giving your ssh password a few times, you should find “new_local_folder” copied into the current path.

Beyond…

If you’re not familiar with SVN commands themselves, the maintainers provide a top-notch Subversion Book that is both tutorial and reference. Also by now, you’re probably sick of typing your ssh password. You can improve this by using authorized keys and ssh-agent. The previously linked Apple article finishes with a section titled “Xcode and Subversion”, though there might be an incompatibility between Xcode and the latest SVN software. Let me know how it goes if you make it that far, or get stuck along the way!